Limited Edition Photography

Limited Edition Photography

The story of limited editions is a record of the ongoing tension between photography's democratic potential for mass distribution and the powerful, enduring appeal of exclusivity in the art world.

What Is Limited Edition Photography?

Limited Edition Photography refers to fine art prints that are released in a predetermined, finite number.

Each print is signed, numbered, and accompanied by a Certificate of Authenticity (COA) issued by the artist or their representing gallery.

Once the edition sells out, no further prints of that image are produced in the same size or format.

This limitation turns a photograph, an infinitely reproducible medium, into a scarce collectible asset, granting it intrinsic and financial value.

For photography collectors, that scarcity represents both exclusivity and investment potential; for photographers, it provides a disciplined, transparent business structure.

When an artist limits an edition to, say, 3 or 5 prints, each print gains exclusivity.

As the edition sells through, prices typically rise, a structured appreciation model that rewards early collectors and reinforces market trust.

Limited edition laws vary internationally. In France, the total edition size, including all formats and proofs, must be disclosed to maintain the work’s classification as a “limited edition artwork.”

California’s Fine Prints Act requires similar transparency for photographic editions sold within the state.

Ethically, the principle is simple: once a limited edition sells out, no further prints of the same image should be produced in that format.

Breaching this principle can permanently damage an artist’s credibility and collector confidence.

Collecting Limited Edition Photography

For collectors, acquiring limited edition photography combines aesthetic appreciation with investment potential. The following criteria are essential when evaluating a purchase:

-

Artist Reputation: Track record, exhibition history, and representation.

-

Edition Size and Structure: Clarity about number of prints, variants, and proofs.

-

Production Standards: Archival quality and printing method.

-

COA and Provenance: Verified documentation and transparent history.

-

Condition: Proper storage and framing to maintain archival integrity.

Collectors increasingly view limited edition photographs as an accessible entry point into fine art collecting, combining visual impact with tangible scarcity.

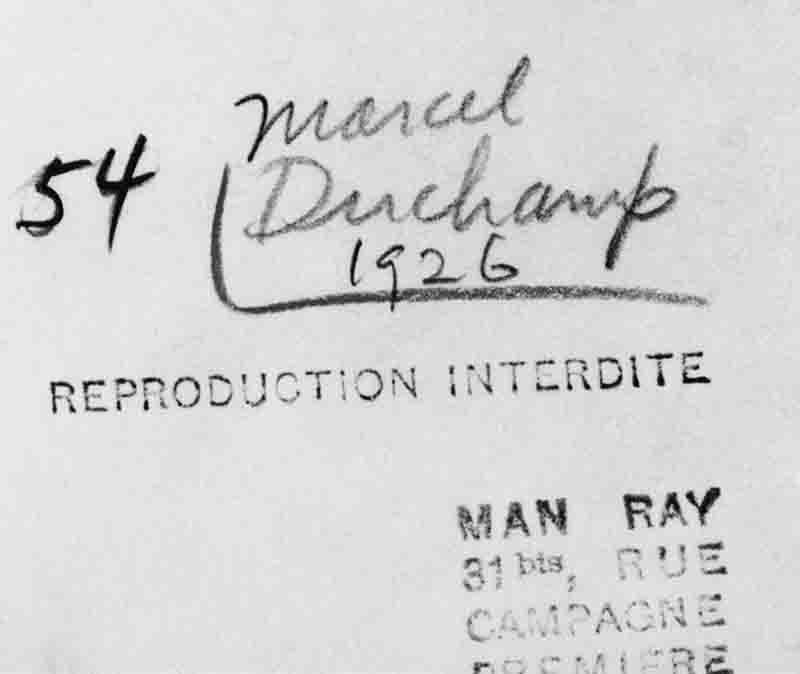

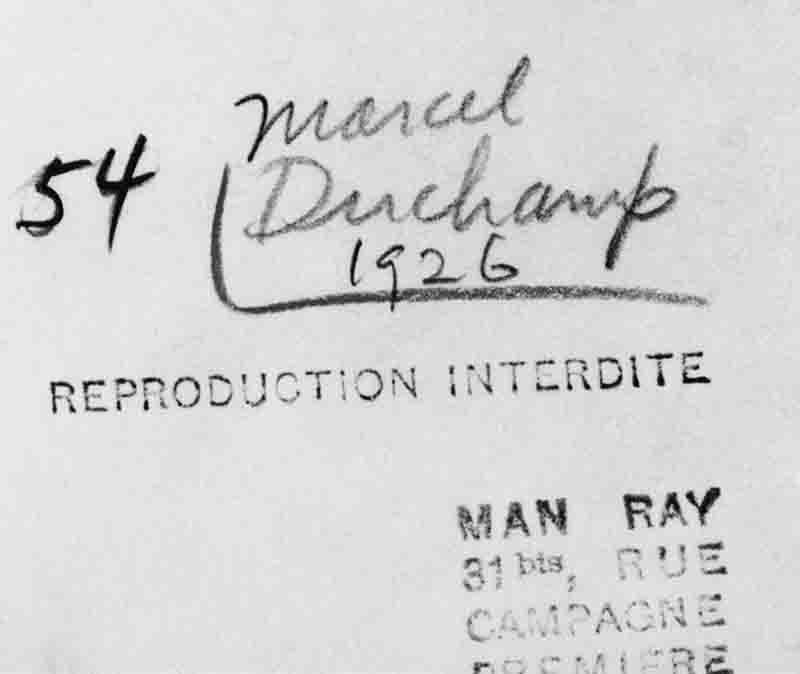

For collectors and galleries, a photograph’s worth often begins with a number, a fraction scrawled beneath the artist’s signature. “1/3” signals exclusivity: one of three authorized prints, each accompanied by a certificate of authenticity.

12 essential facts about Limited Edition Photography

-

Defined by Scarcity: A limited edition means the photographer has committed to producing only a fixed number of prints of a specific image. Once that number is reached, no additional prints of the same format are legally or ethically produced. This controlled scarcity is what creates collectible value.

-

Signed and Numbered: Every limited edition print should bear the artist’s signature and a number (e.g., 3/25), indicating its unique position within the edition. This numbering confirms authenticity and helps buyers verify that their print belongs to the stated edition.

-

Certificates of Authenticity: A Certificate of Authenticity validates the print’s origin and guarantees its legitimacy. It includes details such as edition size, print number, medium, paper type, and date of production. A missing or incomplete COA can dramatically reduce a print’s resale value.

-

Smaller Editions: In general, the fewer prints available, the more valuable each becomes. Editions of 5–15 prints are typically considered highly collectible, while larger runs (e.g., 50–100) make the work more accessible but less scarce.

-

Artist Proofs: Artists may produce a small number of Artist Proofs, often limited to 10% of the edition. These are usually kept by the artist or sold at a premium. Importantly, A/Ps must be declared and tracked to maintain transparency.

-

Archival Quality: Collectors expect museum-grade materials, archival papers, pigment inks, and proper printing techniques (such as giclée or silver gelatin). These ensure the photograph retains its color and integrity for decades.

-

Provenance: Provenance, the documented ownership history of a print, adds credibility and stability to its market value. Maintaining accurate records, COAs, and edition logs is crucial for both artists and collectors.

-

Ethical Limits: Once a limited edition sells out, no more prints of that image (in that size and format) should ever be made. Breaching this rule, by reprinting or issuing unannounced variants, can destroy collector trust and devalue the artist’s entire catalog.

-

Transparency: Countries like France and U.S. states like California have specific laws requiring full disclosure of edition sizes, printing methods, and Artist Proof counts. Even where not mandated, these disclosures are a best practice globally.

-

Digital Authentication: Blockchain and digital certificates are increasingly used to record edition numbers, ownership transfers, and print details. These technologies offer a tamper-proof system for verifying authenticity and provenance in both physical and digital art markets.

-

Value Consistency: Galleries expect artists to maintain consistent editioning policies, same numbering style, clear COA format, and transparent record-keeping. Consistency builds professional credibility and reassures buyers that the artist operates ethically.

-

Art and Investment: For collectors, these works combine emotional and aesthetic appeal with tangible investment potential. Properly documented and preserved, limited edition photographs can appreciate over time, especially when created by artists with growing reputations.

Limited Edition Photography is about trust, documentation, and craftsmanship. It elevates a reproducible image into a collectible artwork, through scarcity, authenticity, and ethical integrity.

Limited Edition Photography Timeline

| Year |

Milestone |

| 1900–1920s |

The idea of limiting prints to preserve artistic value emerged; editioning began informally for prestige. |

| 1930s–1940s |

Most prints were produced for archival or documentary purposes, not limited sales. |

| 1950s–1960s |

Editioning became more formalized, especially among fine art photographers who signed and numbered their prints to assert authorship. |

| 1970s |

Editioning became an accepted commercial and artistic standard; COAs started to appear. |

| 1980s |

Edition sizes were carefully controlled, increasing exclusivity and market value. The secondary market for photography expanded. |

| 1990s |

The rise of digital reproduction prompted renewed focus on authenticity and COAs; collectors demanded transparency about edition limits. |

| 2000–2010 |

Expanded collector base; editioning standards diversified internationally. Some artists used mixed-media or multi-format editions. |

| 2010–2015 |

Blockchain COAs strengthened trust and prevented forgery; provenance tracking entered the digital age. |

| 2020–2025 |

Limited edition photography evolved into a hybrid art form, combining traditional craftsmanship with digital provenance systems to ensure transparency and traceability. |

The concept of a limited edition becomes both physical and digital, anchored in verifiable authenticity and ethical transparency.

The Economics of Scarcity

Buying Limited Edition Photography

Buying Limited Edition Photography

The limited edition system was originally intended to stabilize a medium once regarded as infinitely reproducible.

The Aura of Scarcity: A Modern Solution to an Old Problem

For photography to ascend to the highest echelons of the art market, it first had to solve the riddle of its own nature.

If a single negative or digital file can produce an endless stream of identical prints, how can any single one be considered rare or uniquely valuable?

The art market, in a stroke of commercial genius, devised a solution: the limited edition.

This self-imposed restriction on production artificially creates the scarcity necessary for value to accrue.

By declaring that only a finite number of prints will ever be made, the artist and the market create a collectible, transforming a copy into a kind of original.

This practice is a direct response to a dilemma identified nearly a century ago by the philosopher Walter Benjamin.

In his seminal 1935 essay, "The Art Work in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility," Benjamin argued that mechanical reproduction destroys the "aura" of a unique artwork, its singular presence in time and space.

The limited edition is a deliberate market strategy engineered to restore a form of this aura to the photographic print.

The small number on the back of a photograph serves as a promise of exclusivity, assuring the collector they possess something rare, even if it is not technically unique.

But this system—the very engine of the contemporary photo market, is a modern invention, born from a crisis of value.

Its adoption marks a pivotal moment in photography's long journey from a tool of documentation to a dominant force in the art world.

A Market Divided: The Bright Line Between Vintage and Contemporary

The history of the photography market can be split into two distinct eras, with the dividing line drawn somewhere around 1970.

Before this point, in the age of "historical photography," most works were not created with an art market in mind.

Value was assigned retrospectively, based on factors like age and historical importance.

After 1970, as a robust gallery and auction system for photography emerged, artists began creating "contemporary photography" with the market’s rules in mind from the outset, chief among them the principle of the limited edition.

The Value of Time: Forging Rarity with the "Vintage Print"

In the pre-1970 market, the concept of a limited edition was largely foreign.

The value of a historical photograph is instead often determined by when the print was made.

The market places the highest premium on a Vintage Print, defined as a print created by the photographer at or very near the time the negative was made.

Prints produced years or decades later are categorized as Later Prints and are considered far less valuable, even if they originate from the same negative.

Legendary American landscape photographer Ansel Adams provides a perfect illustration.

Adams was philosophically opposed to limiting his editions, believing it ran contrary to the democratic nature of the photographic medium.

He once compared destroying a negative, the only way to truly guarantee a limit, to destroying a musical score after a performance.

Because he rarely limited his output, some of his most famous images, like "Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico 1941," exist in over 1,000 prints made throughout his lifetime.

Yet, where no limit was intended, the market imposed one. The stark difference in value between an early print of "Moonrise" and a later one demonstrates how scarcity can be forged by time alone.

| Print Type |

Auction Price (USD) |

| Vintage Print |

$300,000 |

| Later Prints |

$18,000 – $85,000 |

The "Vintage" designation functions as a form of retrospective editioning.

It creates a small, finite, and therefore highly valuable subset of prints from a much larger, unlimited pool.

The value lies not just in the image, but in its specific material history and its proximity to the moment of creation.

The Edition Ascendant: Photography as a Market Force

Beginning around 1970, a powerful cultural shift began to elevate photography's status in the art world.

Catalysts like the Museum of Modern Art’s monumental "Family of Man" exhibition in 1955, combined with the rise of photojournalism in magazines like LIFE, created a new "photographic generation" with a sophisticated visual vocabulary.

This generation, primed by images, began to demand them as art.

As galleries dedicated to the medium opened and auction houses held their first photography-only sales, artists started creating work specifically for this emerging market, borrowing the practice of the small, limited edition from the world of fine art printmaking to signal their status as serious works of art.

This strategy proved astonishingly successful, paving the way for photography to achieve price levels once reserved for painting and sculpture.

The financial stakes are now immense, as evidenced by a series of record-breaking auction results.

Defining the Line: The Contentious Details of an Edition

The simple number on the back of a photograph—2/3, for example, seems to offer a clear promise of scarcity.

In practice, however, it masks a host of ambiguities that can lead to bitter conflict between artists, dealers, and collectors.

The lawsuit Sobel v. Eggleston brought a simmering debate to a boil: does a collector own an exclusive right to an image, or merely to a specific object printed in a specific way?

A Battle of Dimensions: The Lawsuit Over Size and Technique

In 2012, collector Jonathan Sobel sued the pioneering color photographer William Eggleston.

Sobel owned prints of Eggleston's iconic images from earlier, limited editions, produced as small "dye transfer prints."

He filed suit after the artist released a new series of the same images as monumental, large-format "pigment prints."

For Sobel, this was a breach of a unique pact.

He argued that the new prints devalued his collection by violating the original promise of exclusivity.

The conflict centered on two competing philosophies of limitation:

Motif-based limitation: The belief that the edition limits the image itself, regardless of format. In other words: "This is the only version of this image you will ever see for sale."

Format-based limitation: The belief that each specific size or printing technique can constitute its own separate edition. In other words: "This is the only version of this image at this size you will see for sale."

In a first-instance ruling, the judge sided with Eggleston, determining that the new prints constituted a "Subsequent Edition" because their size and printing technique differed significantly.

The distinction has profound implications.

A collector's belief in owning one of just ten prints can be shattered if the artist later re-releases the same image in a new, perhaps more impressive, format, highlighting a critical gray area where an artist's right to reinterpret their work clashes with a collector's expectation of exclusivity.

The Invisible Prints: Artist's Proofs and Market Realities

Another layer of complexity is added by the existence of Artist's Prints or Artist's Proofs (A.P.s).

Traditionally, these are a small number of prints made outside the main numbered edition for the artist's personal use, for exhibition, archives, or as gifts.

Historically, they were marked hors de commerce ("not for commerce").

In today's market, however, it is widely accepted that these A.P.s may eventually be sold, effectively increasing the total number of prints in circulation.

This creates a transparency problem, especially when the number of A.P.s is significant.

For example, Richard Prince, an artist famous for his "Appropriation Art" of re-photographing existing images, issued his "Untitled (Cowboy)" in an edition of 2 + 1 A.P. That single Artist's Proof represents a 50% increase in the number of prints available to the market.

For collectors paying a premium for rarity, the existence of these "invisible" prints can feel like a breach of the trust that a limited number is supposed to signify.

Democratizing the Edition: From High Art to Wall Art

While the high end of the market grapples with multi-million dollar sales, the concept of the limited edition also fuels business models designed for broader accessibility.

From ultra-exclusive works to decorative prints sold in the hundreds, the idea of a limited run remains a powerful marketing tool, conferring a sense of quality and collectibility even at lower price points.

The Ghost in the Machine: Photography's Physical Frailty

Beneath the legal wrangling lies a more elemental threat: the photograph is a ghost in the machine, a fugitive medium locked in a losing battle with time.

Unlike an oil painting, which can last for centuries, a photograph, especially a color print, is a delicate chemical object highly susceptible to fading from exposure to light, humidity, and atmospheric pollutants.

This physical vulnerability, this fleeting material presence, is the very embodiment of Walter Benjamin's aura. But it also creates a direct conflict with the desire for absolute edition limits.

The central dilemma is this: the only way to definitively cap an edition and guarantee its conceptual aura of scarcity is to destroy the negative or the master digital file.

Yet doing so would mean that once the existing prints inevitably fade or are damaged, the physical artwork could be permanently lost.

To navigate this conflict between preserving the idea and preserving the object, the market has devised several solutions:

Exhibition Prints: Artists create additional, unsigned prints of a work that exist entirely outside the numbered edition. These copies are made purely for display in museums, allowing the valuable editioned prints to be kept in archival storage, safe from the damaging effects of light. In many cases, these exhibition prints are destroyed after the show concludes.

Replacement Prints: Some artists offer a service to collectors: if an editioned print has faded or been damaged, they will provide a new print at cost. This is done on the strict condition that the collector returns the original print to be destroyed, ensuring the total number of prints in circulation does not increase.

The Digital File: A more modern solution involves providing the collector with a high-resolution digital file ("scan data CD") and precise printing instructions. This allows the owner to create their own replacement upon destruction of the original, a practice that radically questions traditional notions of authorship and authenticity in the digital age.

These practices are workarounds, attempts to reconcile the ideal of a fixed limit with the material reality of a fugitive medium, preserving both financial value and physical existence.

The Power of a Promise

The limited edition is the commercial and conceptual bedrock that allows photography, an infinitely reproducible medium, to function as a high-value asset class.

It is a market-driven convention that imbues a print with an aura of scarcity, transforming it from a mere copy into a coveted object.

From the multi-million-dollar works of contemporary masters to more accessible decorative art, the simple fraction on the back of a photograph is a powerful signifier of value.

Ultimately, this entire multi-billion dollar market is built on trust, the belief that artists, galleries, and auction houses will honor the promise signified by that number.

As the market has matured, this promise has been tested by legal challenges, complicated by market practices, and adapted to contend with the physical fragility of the medium itself.

The story of the limited edition is a story of the ongoing, and often fraught, tension between photography's democratic potential for mass distribution and the powerful, persistent allure of exclusivity in the art world.

By declaring an edition finite, photographers align their work with the economic logic of painting or sculpture, where rarity supports value.

Limited Edition Photography: FAQ

Limited edition photography refers to a set number of prints produced from a single image. Once the edition is sold out, no more prints of that size or format are created. Each print is individually numbered (e.g., 1/5) and signed by the artist, ensuring scarcity and enhancing value.

An open edition allows unlimited reproductions, meaning the same image can be printed indefinitely. By contrast, a limited edition is restricted to a finite number of prints, preserving exclusivity and collectibility. Limited editions typically come with documentation, such as a Certificate of Authenticity, to prove their status.

A COA is an official document issued by the artist or gallery that verifies a print’s authenticity. It includes details such as the edition size, number, title, printing technique, and artist’s signature. The COA serves as proof of originality and is essential for resale, insurance, and provenance records.

To verify authenticity: check that the print is hand-signed and numbered by the artist, review the COA for edition details and issuing authority, confirm provenance through ownership or exhibition records, and verify registration in a digital or blockchain-based registry if available.

Value is influenced by edition size, artist reputation, print quality, condition and framing, and provenance. Smaller editions, archival materials, and well-documented ownership history usually increase collectibility and value.

Yes, often. Artist Proofs are prints outside the numbered edition, usually limited to 10% of the total run. They are typically retained by the artist and sometimes viewed as more exclusive or collectible, depending on demand and artist reputation.

Common printing methods include Giclée (pigment inkjet) for fine detail, silver gelatin for black-and-white prints, C-type (chromogenic) for color images, and platinum/palladium for archival quality and tonal richness. Each process affects texture, longevity, and aesthetic quality.

To preserve quality: frame using UV-protective, museum-grade glass, use acid-free mats and backing, avoid exposure to direct sunlight or humidity, and store prints flat in archival sleeves or boxes. Proper care prevents fading and degradation.

Yes, limited edition photographs can appreciate in value as scarcity and demand increase, especially for recognized photographers. However, appreciation depends on artist reputation, market trends, and condition, so buyers should prioritize authenticity and artistic quality.

Before buying, ask about edition size and number, whether a signed Certificate of Authenticity is included, what printing process and materials were used, if the artist has a market record, and whether there are any Artist Proofs or variant sizes. These questions ensure transparency and protect your investment.